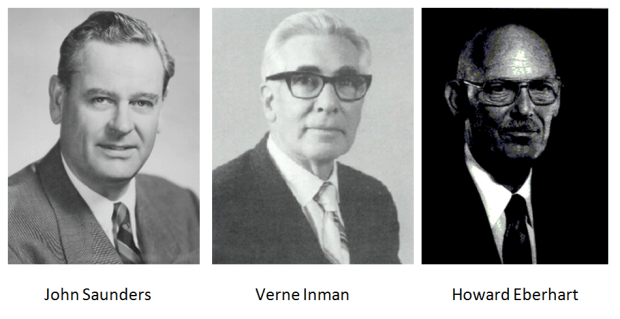

The month of July 2013 marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of The Major Determinants of Normal and Pathological Gait by J B dec M Saunders, Verne Inman and Howard Eberhart. This is a seminal paper in the history of gait analysis which was revered for many years and is the foundation of the description of normal walking in many text books. More recently, however, it has come in for substantial criticism.

The first named author, John Bertrand deCusance Morant Saunders, was a medically trained Professor of Anatomy at the University of California who was born in South Africa of Scottish descent. The story is that he needed his name on a paper to justify a trip to the Joint Meeting of the Orthopaedic Associations in London in 1952 and Inman and Eberhart obliged. There is little doubt that the ideas were those of Inman, a pioneering Orthopaedic Surgeon, and Eberhart, an engineer. (Inman first met Eberhart when amputating his leg after a wartime accident at the time when he had been asked to establish the National Research Council Advisory Committee on Artificial Limbs. He invited Eberhart, originally a civil engineer, to join him and the partnership continued for the next thirty years).

Over the month I intend to write a series of posts celebrating this anniversary by looking at different aspects of the paper. In this post I’d like to dispel one of the myths about the paper which is that it states that the aim of walking is to minimise the excursion of the centre of mass. In a significant review article, for example, Art Kuo (2007) writes “The six determinants of gait theory proposes that a set of kinematic features help to reduce the displacement of the centre of mass. It is based on the premise that the horizontal and vertical displacements are energetically costly”.

An earlier paper by Ortega and Farley (2005) starts with an almost identical quote which drove the authors to train participants to walk with a nearly flat trajectory of the centre of mass. They then showed that it took nearly twice as much energy (oxygen) to walk a given distance with the flattened trajectory than with the normal trajectory. Gordon, Ferris and Kuo (2009 – who I think did the work earlier but published it considerably later than Ortega and Farley) conducted a very similar study and came up with essentially the same results. The introduction of that paper is interesting in describing how “at least a dozen text books have interpreted [Inman’s] work as meaning it is desirable to minimise or reduce COM movement during walking” and giving an overview of how the ideas have developed through these.

What is interesting though is that nowhere in the original paper (nor in the extended versions that have appeared in the three editions of the book Human Walking) can I find any statement by the authors that minimisation of the COM movement is the aim of walking. What thy actually said was this:

Translation of a body in straight line with the least expenditure of energy may be achieved mechanically by the use of a wheel, but it is quite impossible by means of bipedal gait. The next most economical method would be the translation of the body through a sinusoidal pathway of low amplitude in which the deflections are gradual. Since force is equal to mass times acceleration and acceleration is a function of time, abrupt changes in the direction of the centre of motion compel a high expenditure of energy. In translating the centre of gravity through a smooth undulating pathway of low amplitude the human body conserves energy; and, as we shall see in considering pathological gait, the body will make every attempt to continue to conserve energy.

What they are proposing is that the body acts to ensure a smooth trajectory not necessarily one of minimal vertical displacement. They start off by describing compass gait, moving with fixed knee with no foot and the problem that they identify with this is that “at the point of intersection with the arcs, the abrupt change in the direction of the forward acceleration [I think they actually mean vertical component of velocity – RB] would require the application of a force of considerable magnitude”. This is actually extremely close to the hypothesis of the Dynamic Walking Group that one of the principal energy costs of walking is the requirement to redirect the centre of mass velocity during step to step transitions (Kuo et al. 2005) despite a contention that their approach is the antithesis of Inman and Eberhart’s (see Kuo 2007). The six determinants proposed in the original paper are then strategies to smooth the trajectory of the COM but not necessarily to reduce it.

So where did the original and perfectly sensible views of Inman and Eberhart get distorted? Gordon et al. (2009) quote Perry (1992) as saying “minimising the amount that the centre of gravity is displaced from the line of progression is the major mechanism for reducing the muscular effort of walking, and consequently, saving energy”. Perry, of course, trained under Inman, and it may be that like so many pupils it is she that has misrepresented the ideas of her teacher. As an engineer myself, however, I’d take the personal side out. I’d see the original and valid ideas as indicative of the potential for progress when clinicians and engineers come together to address the challenges of clinical biomechanics. The misrepresented and invalid ideas appear when clinicians think they can go it alone!

That’s it for this post. I’ve emphasised one particular aspect in which I think the work has been unfairly criticised. In later posts I’ll look at some aspects where criticism may have been more justified as well as examining the popular appeal of the approach

.

Gordon, K. E., Ferris, D. P., & Kuo, A. D. (2009). Metabolic and mechanical energy costs of reducing vertical center of mass movement during gait. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 90(1), 136-144.

Kuo, A. D., Donelan, J. M., & Ruina, A. (2005). Energetic consequences of walking like an inverted pendulum: step-to-step transitions. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 33(2), 88-97.

Kuo, A. D. (2007). The six determinants of gait and the inverted pendulum analogy: A dynamic walking perspective. Hum Mov Sci, 26(4), 617-656.

Ortega, J. D., & Farley, C. T. (2005). Minimizing center of mass vertical movement increases metabolic cost in walking. J Appl Physiol, 99(6), 2099-2107.

Perry, J. (1992). Gait Analysis. Thorofare: SLACK.

Saunders, J. D. M., Inman, V. T., & Eberhart, H. D. (1953). The major determinants in normal and pathological gait. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 35A(3), 543-728.