An early unit of our Masters Programme in Clinical Gait Analysis has focused on how best to capture clinical video. One of the things we talked about was parallax and I was surprised at how little awareness there was of this as an issue. Parallax describes a number of phenomena associated with how what you see changes with your line of sight. Wikipedia is filled with examples from astrophysics. The video below shows some fairly gentle examples of how the relationship of foreground and background objects changes as your point of view moves.

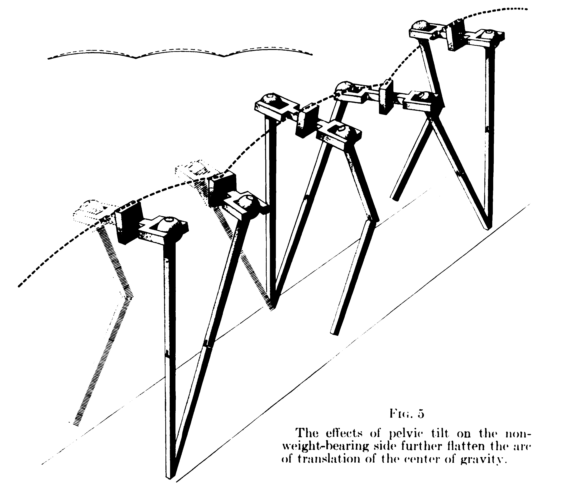

In clinical gait analysis the main effect we are concerned with is that how we perceive a given angle depends on the position we are viewing it from. Thus if the knee is flexed to 90° in the sagittal plane and we are looking from a position perpendicular to that plane then we will perceive the angle to be 90° but if we are looking from either a little in front or a little behind then we will perceive the knee to be more extended. More than that, if the thigh is internally rotated so that the knee is not flexing in the true sagittal plane then we will under-estimate knee flexion even if we are square on to the person. We perhaps understand this best in relation to the coronal plane where most of us know that if the knee is flexed then we will see what appears to be varus or valgus if either we are not looking straight on at the person or if the thigh is internally (or externally) rotated.

To help understand and also to quantify effects I’ve prepared the little Flash animation below. Imagine there is an object in the centre of your gait lab composed of two red rods set exactly at right angles. As you first see the animation the camera is rotating around the object and you can see how the view seen by the camera changes. You can see that even though the object in the lab is entirely stationary the angle read off the computer screen varies from 0° to 90°. If you click on the pause button the animation will stop and you’ll then be able to drag the camera to whatever position you want. Play around with this and see how the perceived angle changes with the camera angle.

What you should find is that the effects are relatively small in the sagittal plane. If you have the camera within +/-13° to the true perpendicular then you will perceive an error of less than 1°. You need to be more than 24° off true to be more than 5° out. Positioning the camera to get a true coronal plane view, however, is much more critical. Being just 5° out in camera alignment will result in an erroneous reading of either 10° of knee varus or valgus (depending on which side of the walkway the camera is viewing from). For those concerned with symmetry of gait remember you get a double whammy as you’ll see an apparent 10° of valgus on one side and of varus on the other side. I must admit than in constructing the animation the effects in the coronal plane are quite a lot bigger than I was expecting. (For the geeks the animation is based on an isometric projection – perspective effects with a camera close to the person could exaggerate the effects even further.)

Of course this varus-valgus thing is the cause of all those huge coronal plane knee artefacts that we all get in swing when we are doing gait analysis. If your don’t identify the coronal plane of the thigh properly from the markers you place for your static calibration you are effectively causing your gait analysis system to look at the knee from the wrong angle and all that knee flexion that occurs in mid-swing will appear as varus or valgus on your knee traces. If you see this happening a lot in the gait data then its worth reviewing how you place these markers.

For those of you not at ESMAC Eric Desailly presented quite a nice paper (page 33) showing that although this effect is a significant factor contributing to those dodgy looking knee trace it may not be the only one.