The arguments against the Determinants that I described in my last post are largely technical. It is interesting that the latest editions of three mainstream textbooks (Levine, Richards & Whittle, 2012, Kirtley, 2006 and Rose & Gamble, 2006) all print fairly damning critiques of the Determinants but choose to reproduce them anyway. Kirtley dedicates nearly four pages to describing them and then describes them in the last paragraph as “thoroughly discredited”. Does this mean that despite the technical problems the Determinants are still useful in some way? Might they reveal some clinical truths? Let’s explore some more general issues.

One of the problems I see with the Determinants is that the basic “compass gait” (reciprocal flexion and extension of the hips) often gets overlooked. The original authors describe it quite superficially in a couple of sentences and then move on to much more extensive discussion of the Determinants. Levine, Richards and Whittle skim over it in even less detail and Kirtley doesn’t really describe it at all. The balance should really be the other way round. Reciprocal hip flexion and extension is the most fundamental characteristic (determinant?) of bipedal walking. To a large extent step length is determined by the range of motion you achieve at your hips (modified to a much lesser extent by any knee flexion at initial contact) and cadence by the rate at which you can move through this. The first thing anyone should be doing when assessing someone’s gait is to consider how effectively they are implementing this basic mechanism. If you list the Determinants, however, hip flexion and extension never appear.

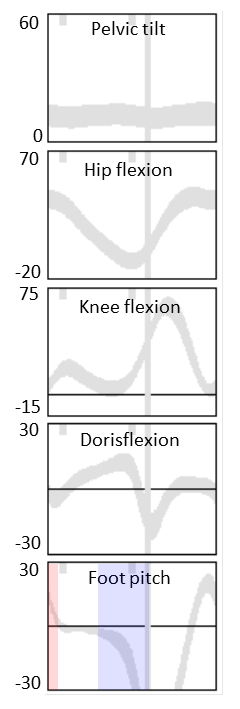

Another rather disconcerting issue is how the Determinants lead you to focus on rather small movements of the pelvis in the transverse and coronal planes when there are much more significant movements at the knee and ankle in the sagittal plane. Whilst pelvic movements play an important role in the fine tuning of gait, the major sagittal plane motors acting to control hip, knee and ankle are where the action is. The fine movements of the pelvis get two Determinants to themselves and are described in precise detail whereas the knee and ankle are rolled together in one muddled paragraph (in the original paper). Any approach to walking that distracts the focus from the hip, knee and ankle is likely to be hindering rather than helping. To this day it amazes me that when I show a video of a person walking with a really bizarre walking pattern, many people start off describing the minor imperfections in the motion of the pelvis, often concentrating on the coronal plane, before moving on to much larger aberrations of hip, knee and ankle movement in the sagittal plane.

Then finally there is the reduction of walking to achieving a single objective (walking at minimum energy cost). As Perry (1985) and Gage (1991) have both pointed out in different ways there are multiple objectives in walking (see my screencasts on the subject for more details). We need to support body weight against gravity, achieve toe clearance and adequate step length and achieve a smooth transition from one stride to the next whilst preserving the momentum of the passenger unit. In pathological walking the requirement to avoid pain or maintain an adequate walking speed given some specific impairment might be more important than minimising energy cost. All of these need to be considered if we want to understand walking.

I better stop before this turns into too much of a rant but (in my opinion) the answer to my original questions are, “No, the Determinants are not useful” and, “No, they are exceedingly unlikely to reveal any further clinical insights”. The sooner someone comes up with an alternative the better. (I’ve had a go [series of seven screencasts] but am the first to admit that my approach lacks the elegant simplicity of the determinants even if I’d defend it as more biomechanically rigorous and clinically relevant).

.

Gage, J. (1991). Gait Analysis in Cerebral Palsy. Oxford: Mac Keith Press.

Kirtley, C. (2006). Clinical gait analysis (1st ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Levine, D., Richards, J., & Whittle, M. W. (2012). Whittle’s Gait Analysis (5th ed.): Churchill Livingstone.

Perry, J. (1985). Normal and pathological gait. In W. Bunch (Ed.), Atlas of orthotics (pp. 76-111). St Louis: CV Mosby.

Rose, J., & Gamble, J. (Eds.). (2006). Human Walking (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.