Every so often I’m asked about why we tend to do clinical gait analysis barefoot and in AFOs (and shoes). One answer is that the barefoot condition tends to give a better indication of the full extent of a patient’s problems whereas walking in AFOs may be a better indication of how they function in everyday life. Another, however, is that sometimes walking in AFOs can help in identifying which particular impairments are having the most effect on gait. This was certainly the case when, a couple of weeks ago, I was reviewing one of the case studies we often use for teaching purposes but which exhibited features that I had not previously understood.

The analysis is of a seven year old girl with diplegic cerebral palsy (GMFCS III). She can take a few steps unaided but normally walks with a K-walker. We actually tested her in and out of the K-walker barefoot and in shoes and AFOs. the K-walker didn’t make that much difference to the kinematics with either condition so we’ll focus on the two unassisted walking conditions.

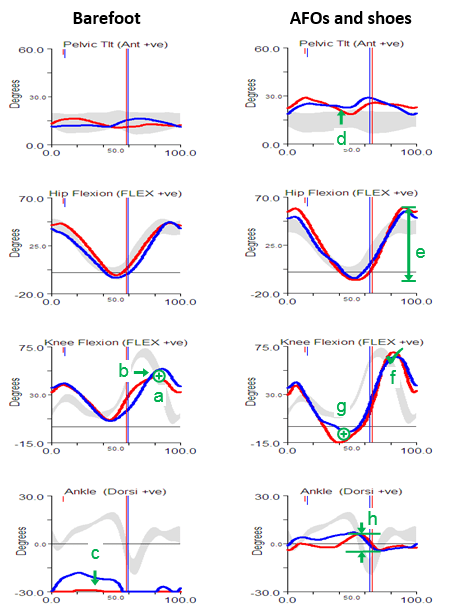

Perhaps the most obvious feature of the barefoot data is that she walks right up on her toes in considerable plantarflexion (feature c). The physical examination data shows that plantarflexor contractures (no passive dorsiflexion with knees extended beyond 10° plantarflexion ) can account for some of this but there are also signs of spasticity (from modified Tardieu and Ashworth tests). There is also, however, some suggestion of late (feature b) and reduced (feature a) knee flexion in swing. There is no clear explanation of this from the physical exam although there is a response to the Duncan-Ely test when performed quickly which might indicate some rectus femoris spasticity. Along with these specific findings the assessment indicates generalised weakness, persistent bilateral femoral neck anteversion and some mild tightness of the hip flexors.

The gait analysis with AFOs is quite different. The solid AFOs cast in a neutral position (which might have been assumed to be too aggressive given the physical examination) do appear to be holding the ankle in neutral and substantially limit movement at the ankle (feature h). The pelvis is a little more anteriorly tilted (feature d), possibly to move the centre of mass anteriorly as the new sagittal plane foot alignment will move the centre of pressure anteriorly (the steps were too short to get reliable kinetics). This would also exert a greater external extending moment at the knee which accounts for the hyperextension in late stance (feature g). The increased pelvic tilt leads to increased maximum hip flexion whereas the hyperextension pushes the knee back and maintains maximum peak hip extension. The overall effect is an increased range of movement at the hip (feature e). Perhaps most interestingly though, given that there is a question as to whether the rectus is spastic or not, is that peak knee flexion in swing is essentially normal (feature f). The slope of the knee graph through toe off is if anything a little steeper than normal. Such free flexion of the knee suggests that rectus spasticity is not a problem. Peak knee flexion is still delayed but this is clearly seen to be a consequence of the knee being too extended as it starts to flex in middle single support rather than of any stiffness. In summary, the data from the barefoot condition is inconclusive as to whether rectus femoris spasticity is contributing to the gait pattern but the data from the AFO condition provides quite strong evidence that it is not.

I hope that this has answered the question I posed at the beginning of this post but it does prompt another question – if there is no rectus spasticity then why is peak knee flexion so reduced in the barefoot condition?

I think the answer to this may lie in the observation that if a person is walking on their toes (and in plantarflexion) then it actually requires considerably less knee flexion for clearance in swing than in normal walking. In other words this girl may be showing reduced knee flexion in swing simply because she doesn’t need it when walking barefoot not because there is anything wrong with her knee function.In AFOs the ankle is held in neutral which makes clearance much more difficult and she has no option but to flex the knee more. It is interesting to note that when walking with shoes and AFOs she walks 20% slower than in bare feet and looks considerably less stable and fluent in her movements.

Rather than waste a lot of text in trying to explain why this occurs I’ve recorded a short video using Verne to illustrate that this is the case.

I go into the underlying concepts in relation to normal gait in this screen cast and have explored some of the other consequences of this for those walking in a more crouched gait pattern in this video blog.