Whenever I give my “Why we walk the way we do” lecture as I did again last week at our gait course (click here to read some of the delegates comments from the Course Evaluation Forms) it makes me think in more detail of some of the biomechanics. This time it made me think more about the swing phase pendulum. In a sense this mechanism is too obvious and we perhaps don’t think enough about it.

There is a historical perspective. The Weber brothers, writing in 1836, assumed a simple pendulum action and came up with a lot of calculations based on elementary physics to support their assumption. Shortly afterwards, however, Guillame Duchenne, noted that he had several patients with isolated flaccid paralysis of the hip flexors who had to walk with circumduction to clear their limb. This suggested an active rather than passive mechanism. It was this question that drove the amazing work of Braune and Fischer in the late 19th century. They confirmed Duchenne’s clinical observation that initiation of swing is an active process.

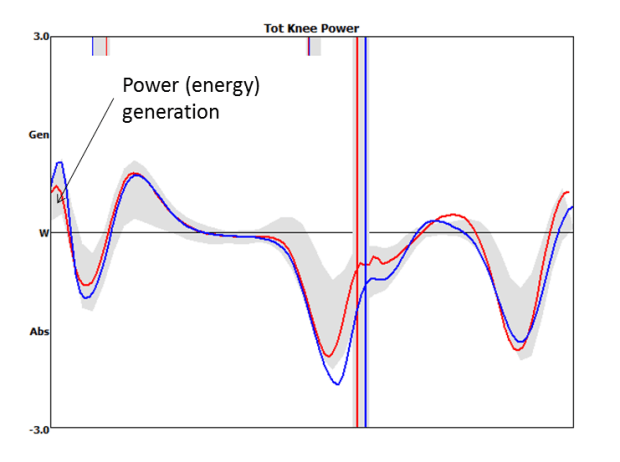

In my lecture I gloss over this a bit leaving the assumption that the pendulum motion during swing is an energy conserving process. It struck me this year that an indication of whether this is the case is to look at the hip moment. A good definition of a simple, energy conserving pendulum is one in which no moment is exerted at the pivot (hip). Looking at the hip moment (above, taken from the notes I prepared for the course) it appears to have three phases in swing. In early swing a marked hip flexor moment is exerted accelerating the limb, through middle swing the moment is essentially zero (we do have a simple pendulum movement) and in late swing the hip extensors are active to decelerate the limb.

In a paper that I’ve only just discovered, Holt et al. (1990) do some calculations to estimate natural frequency of the lower extremity and suggest that the actually frequency of swing is about 40% higher. Doke et al. (2005) confirmed this and also showed that if someone just stands and swings their leg then energy consumption is indeed very low at this frequency and considerably higher at frequencies more normally associated with those of self-selected walking speeds.

I also seem to remember that when I’ve seen scaled up passive dynamic walking machines (which genuinely do use minimal energy through using a free pendulum mechanism, see video above) they walk much slower than we do. Given the rigour with which these guys normally do their work I suspect that they’ll have some theoretical calculations that suggest that walking could be even more efficient if we walked closer to this resonant frequency. I think the Dynamic Walking group are meeting in Zurich this week, it would be interesting to see if any of them could comment.

We thus reach the same conclusion as Braune and Fischer, that this is a forced pendulum, i.e. that it is being forced to swing considerably faster than its natural frequency. This takes energy and thus the simplistic assumption that having something that looks like a pendulum gives us movement for free is seen to be misleading. It could but it doesn’t.

It reminds us that whilst minimising energy cost is an important factor in determining how we walk it is not the only factor. Using the language of Jim Gage (2009) there are a number of attributes of walking. Energy efficiency is one of these but the dynamics of the double pendulum are also critical to at least two others, clearance in swing and appropriate step length. To understand walking we need to understand the inter-relationships between all these attributes rather than focussing on just one. Maybe one day I will!

.

PS It is also worth noting that it is only a simple or compound pendulum that has a natural frequency. A double pendulum, which is a better model of the swing limb, does not generally have a cyclic motion and has a period that varies somewhat from cycle to cycle. The inverted pendulum is the mechanism by which the mass of the whole body is moved forward and is thus probably more important for the energetics of walking. It does not have a natural frequency at all.

.

Doke, J., Donelan, J. M., & Kuo, A. D. (2005). Mechanics and energetics of swinging the human leg. Journal of Experimental Biology, 208, 439-445.

Gage, J. R., Schwartz, M. H., Koop, S. E., & Novacheck, T. F. (2009). The identification and treatment of gait problems in cerebral palsy. London: Mac Keith Press.

Holt KG, Hamill J and Andres RO (1990). The forced harmonic oscillator as a model of human locomotion. Human Movement Science 9:55-58