Here are two graphs. The first from very early in my career shows a parameter we called the “dynamic component” of gastrocnemius length. It plots the improvement in this after injection of botulinum toxin in children with cerebral palsy against the baseline score (Eames et al., 1999). I remember when Niall first showed me the graph. We’d captured a whole load of data on these kids and were wondering what to plot to make sense of it. This was the first suggestion and I can still remember Niall’s excitement when it came up with such a strong relationship.

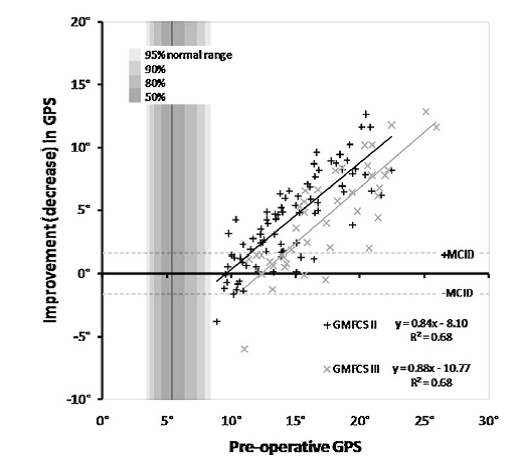

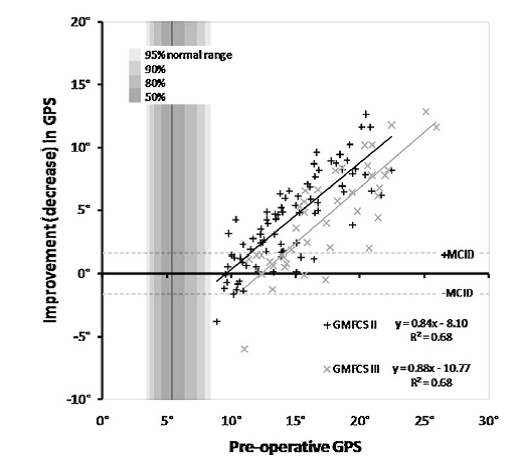

At the other end of my career here’s another graph from a paper that has only just been published electronically in Gait and Posture (Rutz et al. 2013). Here is the improvement in Gait Profile Score (GPS, Baker et al., 2009) for children with cerebral palsy plotted against baseline score (with GMFCS II and III children plotted separately). Again there is a strong correlation. (There are some statistical issues in plotting data this way which might lead to exaggeration of the correlation when measurement error is substantial but I’ve gone to some lengths in the recent paper to show that this is unlikely.)

When you think about it though the relationship is actually quite unremarkable. What both studies are showing is that kids with the most severe problems to start with are the most likely to show improvements. To a certain extent this is common sense – if two kids both improve by 30% then the child with the biggest problem to start with will show the biggest change in absolute units.

What interests me though is that if we only look at the average changes in each group we will reach the conclusion that the group as a whole have improved. If we are not careful we might conclude that all the group has improved. Thissimply isn’t the case. The full truth is that the kids who have the biggest problems have improved a lot those with milder problems haven’t improved very much (in absolute terms).

The Botulinum toxin study became the basis for an industry sponsored randomised controlled trial (Baker et al. , 2002). In that trial although we included baseline readings as a covariate in the statistical analysis but we only ever reported group results. That is still probably the most rigorous trials of lower limb injection of Botulinum Toxin in the literature. The message that almost everyone has taken out of that study from the data we presented is that kids with spastic diplegia will benefit form Botulinum toxin. Had we presented the data more carefully the conclusion should have been that the more severely affected kids will benefit from Botulinum Toxin big time, but that the milder kids may not benefit at all.

As it stands the paper is really convenient for the company because it suggests that a wider group of kids will benefit from an expensive drug than is actually the case. Given that bigger responses to treatment in more severely affected people is likely in almost all conditions that affect people across a range of severity I suspect that a similar phenomena spread across almost all of . I wonder how much profit the drug companies are making as a consequence?

Leave a comment or double click “n comments” link at top of post to view discussion.

Baker, R., Jasinski, M., Maciag-Tymecka, I., Michalowska-Mrozek, J., Bonikowski, M., Carr, L., . . . Cosgrove, A. (2002). Botulinum toxin treatment of spasticity in diplegic cerebral palsy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Dev Med Child Neurol, 44(10), 666-675.

Baker, R., McGinley, J. L., Schwartz, M. H., Beynon, S., Rozumalski, A., Graham, H. K., & Tirosh, O. (2009). The gait profile score and movement analysis profile. Gait Posture, 30(3), 265-269.

Eames, N. W. A., Baker, R., Hill, N., Graham, K., Taylor, T., & Cosgrove, A. (1999). The effect of botulinum toxin A on gastrocnemius length: magnitude and duration of response. Dev Med Child Neurol, 41(4), 226-232.

Rutz, E., Donath, S., Tirosh, O., Graham, H.K., Baker, R. (2003). Explaining the variability improvements in gait quality as a result of single event multi-level surgery in cerebral palsy. Gait Posture, published on-line http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.01.014