Writing about the movement of the hind-foot the a couple of weeks ago and about projection angles last week has led me to reflecting a little on Jacquelin Perry’s rockers. As with many of the concepts that we have in gait analysis, the rockers can give us some really useful insight into how we walk but can also prove misleading if we don’t remain conscious of their limitations.

I don’t recognise the word “rocker” as meaning anything in particular in this context and had assumed it was an American word meaning pivot or fulcrum. I happened to mention this to a couple of American colleagues a couple of years ago, however, and found that they didn’t recognise the word either. It would appear that Perry simply made it up. Not that it matters much, the word seems to get the concepts across readily enough.

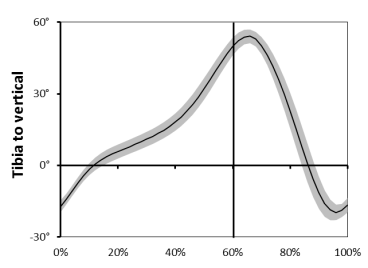

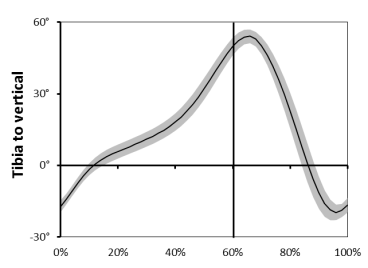

The rockers provide mechanisms for the tibia to move forward over the foot and hence for the passenger unit to be carried forward in stance. If we look at the angle the tibia makes to the vertical (above) then we can see that it starts off about 20° behind vertical at foot contact and progresses forwards reasonably steadily (with a bit of a wobble) to reach about 50° in front of vertical at foot off.

Perry explains this in terms of three rockers. Early on the whole foot rotates about the heel. Later on the tibia rotates over the foot about the ankle and then finally the whole foot rotates about the forefoot (see below). Easy eh!

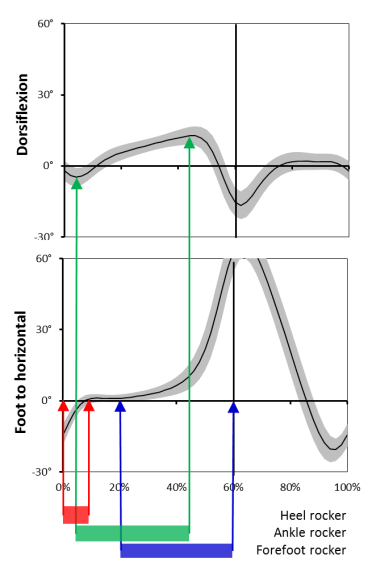

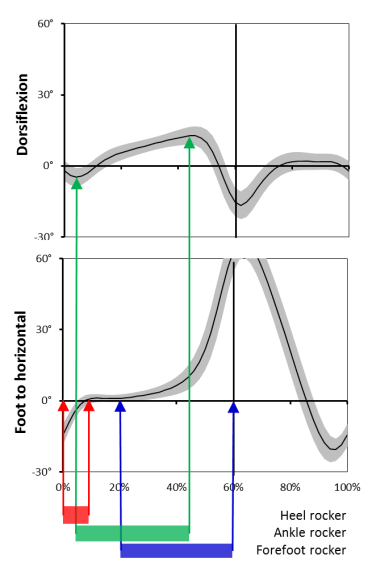

There is no doubt that all three mechanisms make important contributions to tibial progression. I’m not quite so convinced by Perry’s implication that these occur as a sequence of discrete mechanisms. To investigate this we need to look at the dorsiflexion graph which tells us when ankle rocker occurs and the foot projections graph that tells us when the heel and forefoot rockers are active (see graphs below, note that is impossible to distinguish the timing of the rockers from the ankle angle graph alone ).

Heel rocker starts off at foot contact and proceeds until the foot is flat at about 8% of the gait cycle (in red above). It should be noted that this is considerably longer than the period to maximum plantarflexion in early stance that it is sometimes related to. Ankle rocker is the period over which the dorsiflexion angle increases which we can see from the ankle angle graph is from about 5% of the gait cycle to about 45%. There is thus a short period of overlap when both the heel and ankle rockers are active.

Forefoot rocker starts with heel lift which Perry suggests occurs at mid-stance (30% gait cycle). The data depicted above suggests it might commence even earlier (20%?) and it continues until the end of stance. It is thus clear that there is a considerable period from about 20% of the gait cycle until 45% when both ankle and forefoot rockers and simultaneously active.

The conclusion is that whilst the rockers are undoubtedly the mechanisms which allow the tibia to progress they form an overlapping progression rather than a series of discrete events. Indeed for the majority of stance two rockers are active simultaneously.

Since Perry introduced the concepts there has been some slippage in how the terms have been applied which is best avoided. As far as I can see, Perry always talked about heel, ankle and forefoot rockers and never first, second and third rockers. I think this is good practice as quite a lot of our patients don’t have a first rocker (they make contact with the forefoot rather than the heel). It’s always seemed a little illogical to me for someone to have a second rocker if they’ve never had a first rocker!

The other common misconception is that the rockers are alternative labels for phases of the gait cycle. Again Perry never used them in this sense, for her they are mechanisms that allow the tibia to move forward over the foot not phases of the gait cycle. It is particularly erroneous to apply these terms to phases of pathological gait. Many kids with CP never make heel contact and it is thus completely inappropriate to refer to early stance as the phase of heel rocker.

This reinforces the fact that the rockers are mechanisms of normal gait and great care is required in applying the terms to walking with pathology. If a child with CP makes contact with the toe after which the foot comes flat later in stance then they must use a mechanism that might best be described as a reverse forefoot rocker during which the heel is being lowered to the ground rather than being raised. Similarly if they employ a vault to assist clearance of the swing limb then they will often have a reversed ankle rocker during which plantarflexion (rather than dorsiflexion) increases.

Referring back to the work I described in my blog the week before last strongly suggests to me that, in bare feet, the heel rocker is actually a heel roller with the movement being a rolling on the curved surface of the posterior-distal calcaneus rather than a pivot about a particular point on the heel. On the other hand if walking in a shoe with a reasonably stiff heel it is more likely that a rocker like mechanism does occur. The appropriateness of this terminology may thus depend on footwear as well as gait pathology.

PS. In the second edition of Gait Analysis, Perry and Burnfield describe a fourth toe rocker very late in stance. This can certainly be seen on slow motion videos but I’m not aware of any detailed studies of its biomechanical significance. It looks to occur very late on and I suspect only after most of the load has been taken off the foot but it would be nice to see a more definitive analysis of this.