This is a second post “celebrating” the 60th anniversary of the publication of the determinants of gait. I’d intended to start off with something positive in the first post, that the paper has been subjected to some misinterpretation, but Rodger Kram’s comment has made me reconsider that. Perhaps the notion that energy can be conserved by reducing the vertical excursion of the centre of mass is (CoM) implicit in parts of the paper if never mentioned explicitly. This has even led me to speculate on how that might have arisen.

Anyway I’d tried to start with a positive because at some time we have to deal with the negatives. These are quite significant because there can be no real doubt that the determinants are wrong!

If we accept that a belief that minimising the vertical component of the centre of mass trajectory will reduce energy cost is implicit in the paper then the determinants are clearly wrong right from the start. There are multiple examples throughout dynamics of systems in which potential and kinetic energy are exchanged without requiring any external energy (the simple pendulum is the most obvious example). There is absolutely no reason why minimising CoM movement should necessarily reduce energy consumption. Even if CoM excursion did lead to increased energy expenditure we now know that most of the determinants don’t actually reduce it. Gard and Childress (1997) started off by showing that pelvic list occurs at the wrong time and a little time later (1999) that the same is true of stance phase knee flexion. A short time later Kerrigan et al. showed that pelvic rotation has little effect on CoM height either.

The stance phase determinants (pelvic list, stance phase knee flexion) become even more bewildering if the aim is to smooth the trajectory of the CoM, because the trajectory is smooth already. Compass gait results in the CoM moving along a circular arc and there can be few trajectories that are smoother than that!

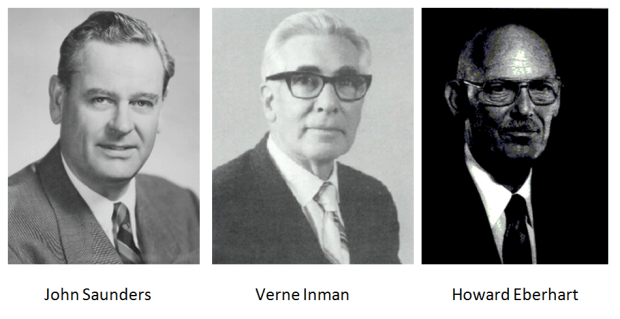

The final nail in the coffin was delivered by both the Chicago (Gard and Childress, 2001) and Boston (Kerrigan et al. 2000) groups establishing that Saunders, Inman and Eberhart had missed the most important determinant of CoM movement which is movement of the foot and ankle and particularly heel rise in late stance.

We thus have a triple whammy:

- the axioms on which the determinants are inappropriate (either because the trajectory of the CoM in compass gait is already smooth or because there is no particular reason why reducing its vertical excursion should reduce energy cost)

- three of the major determinants don’t alter gait in the way the authors claimed

- the authors missed the most important determinant that does!

I’m not the first to outline this of course. Art Kuo made a similar summary in an article in 2007. The most bizarre commentary, however, is that of Childress and Gard published in the third edition of Human Walking (2006). There’s nothing bizarre about the commentary but there is about its location- immediately after a full reproduction of the chapter as published in previous editions. We thus have a “keynote” chapter in a major text-book followed by a two page summary of why the chapter is wrong. How weird is that?

.

Childress, D. S., & Gard, S. A. (2006). Commentary on the six determinants of gait. In J. Rose & J. G. Gamble (Eds.), Human Walking (pp. 19-21). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Gard, S., & Childress, D. (1997). The effect of pelvic list on the vertical displacement of the trunk during normal walking. Gait and Posture, 5, 233-238.

Gard, S., & Childress, D. (1999). The influence of stance-phase knee flexion on the vertical displacement of the trunk during normal walking. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80, 26-32.

Gard, S., & Childress, D. (2001). What determines the vertical displacement of the body during normal walking? Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics, 13, 64-67.

Kerrigan, D. C., Della Croce, U., Marciello, M., & Riley, P. O. (2000). A refined view of the determinants of gait: significance of heel rise. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81(8), 1077-1080.

Kerrigan, D., Riley, P., Lelas, J., & Della Croce, U. (2001). Quantification of pelvic rotation as a determinant of gait. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82, 217-220.

Kuo, A. D. (2007). The six determinants of gait and the inverted pendulum analogy: A dynamic walking perspective. Hum Mov Sci, 26(4), 617-656.