In his comment to my last post BJ said, “I think our field needs some general physiological principles (such as “muscles generate very little passive force during walking”) to help improve the accuracy of our muscle force estimation process”. In his book Rick Lieber states, ” It is difficult to hypothesise, a priori, the ‘best’ sarcomere length operating range of muscle”. So there’s a challenge!

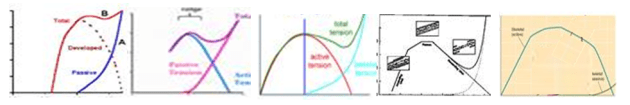

In looking at the issues I realise that I’ve never really seen a simple analysis of how a muscle and tendon work together in series (most I’ve looked at get very complicated very quickly, e.g Winters as quoted by Thelen). So let’s take the well known properties of the force length curves for muscle and tendon (see Figures below) and try and consider how they would lead a simple musculotendinous unit to behave.

Let’s assume the simplest possible arrangement of these as two elements in series held at fixed length. Let’s start off by analysing what happens when this fixed length is what I call musculotendinous unit slack length. This is the minimum separation of origin and insertion at which both the inactive muscle and tendon generate no tension (muscle at optimal length, tendon at tendon slack length to use the jargon).

Its obvious that together the length of the muscle and tendon must equal the fixed length we’ve chosen so it becomes possible to plot the force generated in the tendon as a function of muscle length on the same graph as that for the muscle (see Figure below). It looks steeper because the horizontal scales of the two graphs above are different and it appears to be the wrong way round because as the muscle get’s longer the tendon will get shorter.

Now if any two mechanical elements are in series like this we know that the same force must pass through both (these are the laws of physics and we can’t do anything about them). We can thus say that the force generated by the musculotendinous unit as a whole must be equal to that at the point at which the red line and the blue lines cross for a given level of activation (represented by the blue dots for 0, 33%, 66% and full activation). You’ll see that as the muscle get’s more activated this point moves up and to the left. The tension in the musculotendinous unit increases as the muscle shortens (and hence the tendon lengthens) which is what you would expect.

Notice however that the force must lie somewhere on the blue curve. This restricts quite severely the range of muscle lengths at which the musculotendinous can generate force. Rather counter-intuitively (at least to my simple mind) the operating length of the muscle as a component of the musculotendious unit appears to be more dependent on the force-length characteristics of the tendon than those of the muscle. Notice also that the maximum force that the unit can generate (the point at which the blue line and maximum activation curve for the muscle intersect) is less than that for the muscle acting in isolation.

At musculotendinous unit lengths the only change in the graph is that the blue line will move to the right (if the unit gets longer) or to the left (if the unit gets shorter). An interesting observation here is that if the blue curve moves too far to the right then there will come a point at which there is a minimum force that the unit can generate as well as a maximum. This makes sense in that if you stretch the musculotendinous unit too far you will be stretching the passive parallel component in the muscle regardless of whether it is activated or not.

But let’s take that in combination with the observation I focussed on in last week’s post that when we move the joints passively (through much more than the range of movement required for walking) during a physical examination of a healthy adult we encounter minimal resistance. This suggests that there must be a limit to how far to the right that blue line can be during walking. If we assume the resistance to passive stretch over the range of movement required for walking is less than 5% of the maximum force that the muscle can generate isometrically (I think this is quite a reasonable constraint to impose) then the most right-ward position of the solid blue line is that illustrated in the figure below. You can see that this restricts the operating range of the muscle even more than the logic I applied last week. Last week I argued that the muscle cannot be operating on the passive arm of the the force-length curve. This week I’m suggesting that it cannot be operating on much of the descending arm either.

The thinner dashed curves show the behaviour of the system when the musculotendinous unit is shorter. As well as a line at 5% of maximum muscle force I’ve drawn another in at 50%. The green region is thus intended to show the range of muscle lengths over which the musculotendinous unit is capable of generating this level of force. It suggests that in order for effective force generation by the musculotendinous unit the muscle lengths must lie between about 70% and 110% of optimum length.

The curves, particularly that for tendon, will vary from muscle to muscle (and maybe from individual to individual). The data illustrated here are those use to describe the lateral gastrocnemius in the Gait2392 model which is available through the OpenSim web-site (although I’ve tweaked the characteristics of active muscle force generation to match the widely accepted work of Gordon et al.). I’ve tried it with a semimembranosus as well and get a slightly steeper tendon curve (when scaled to optimum muscle length) but broadly the same conclusions. The analysis assumes isometric contractions of the muscle but given that most of the conclusions are dependent on the characteristics of the force-length curve for tendon rather than that for muscle I can’t see how consideration of the force-velocity characteristics of muscle can make that much difference.

I’d be particularly interested to know if anyone has seen a similar analysis in print anywhere. Have I just been looking in the wrong places?