I get quite a few queries from people asking about how they should construct normative databases with which to compare their measurements. The first question to address is what you want the normative database for. As you’ll read in my book or in a paper that has just been accepted for Gait and Posture (based on the paper I presented at GMCAS last year) I’m not convinced by the traditional arguments that we all have different ways of doing things and that we need to compensate for this by comparing clinical data to our own normative data. The whole history of measurement science, which really started at the time of the French revolution, has been about standardisation and the need to make measurements the same way. I don’t see any reason why gait analysts should be allowed to opt out of this.

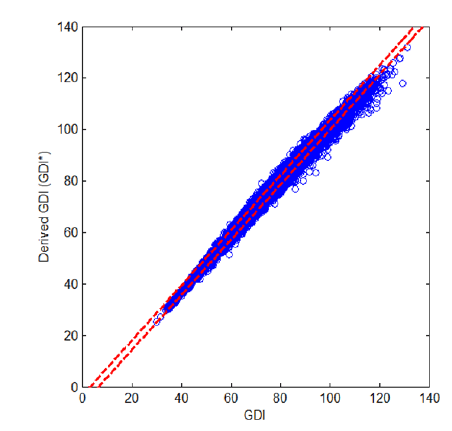

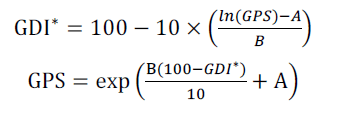

I’d suggest that the main reason for collecting normative data should be to demonstrate that our measurement procedures are similar to those used in other labs rather than to make up for the idiosyncrasies that have developed for whatever reasons. Our paper shows that there are very small differences in normative data from two of the best respected children’s gait analysis services on different sides of the planet (Gillette Children’s Speciality Healthcare in Minneapolis and the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne). The paper should be available electronically very soon (a couple of weeks) and will include the two normative datasets (mean and standard deviations) for others to download and compare with.

There are two important elements for comparison. Differences between the mean traces of two normative datasets will represent a combination of systematic differences between the participants and between the measuring techniques in different centres. If you find large differences here you should compare detailed description of your technique with that from the comparison centre and try and work towards more consistent techniques. Differences in the standard deviations represent differences in variability in the participants and in the measurement techniques. High standard deviations are likely to represent inconsistent measurement techniques within a given centre and require work within the centre to try and reduce this.

Having defined why we want to collect the data you can then think about how to design the dataset. The most obvious question is how many participants to include? The 95% confidence limits of the mean trace are very close to twice the standard error of the mean which is the standard deviation divided by the the square root of the sample size. I’ve plotted this on the figure below (the blue line). Thus if you want 95% confidence that your mean is within 2° of the value you have measured you’ll need just under 40 in the sample. If you want to decrease this to 1° you’ll need to increase the number to about 130. I’d suggest this isn’t a very good return for the extra hassle in including all those extra people.

Calculating confidence limits on the standard deviations is a little different (but not a great deal more complicated) because they are drawn from a chi-distribution rather than a normal distribution (see Stratford and Goldsmith, 1997). We’re not really interested in the lower confidence limit (how consistent our measurements might be in a best case scenario) but on the upper confidence limit (how inconsistent they might be in the worst case). We can plot a similar graph (based on the true value of the standard deviation being 6°). It is actually quite similar to the mean with just over 30 participants required to have 95% confidence that the actual SD is within 2 degrees of the measured SD and just under a hundred to reduce this to 1°.

In summary aiming to have between 30 and 40 people in the normative dataset appears to give reasonably tight confidence intervals on your data without requiring completely impractical numbers for data collection. You should note from both these curves that if you drop below about 20 participants then there is quite high potential that your results will not be representative of the population you have sampled from.

That’s probably enough for one post – I’ll maybe address some of the issues about the population you should sample from in the next post.

Just a note on the three day course we are running in June. Places are filling up and if you want to book one you should do so soon.

.

Stratford, P. W., & Goldsmith, C. H. (1997). Use of the standard error as a reliability index of interest: An applied example using elbow flexor strength data. Physical Therapy, 77, 745-750.