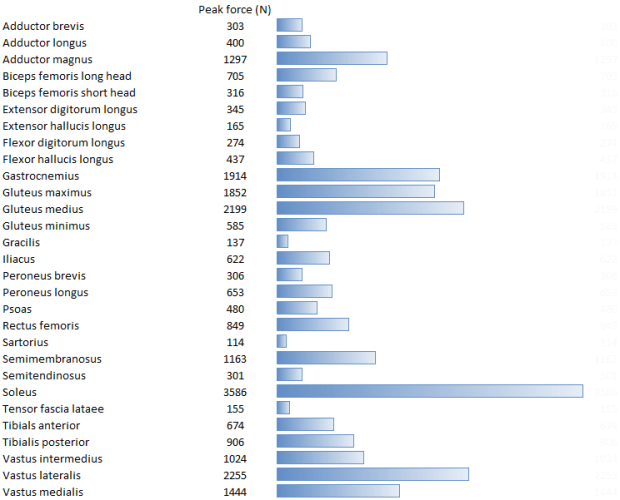

Various things have made me think about muscles this week and an issue that’s puzzled me for some time. Why do we have such big hip adductors? Edith Arnold’s paper (2010) is probably the most authoritative we have on the relative strengths of muscles based on muscle volume and fibre length measurements from 21 cadavers. I’ve tabulated the data below. It’s got a few surprises. The gluteus maximus is the largest muscle but several others are considerably greater capacity to generate force (because they have more shorter fibres), the soleus, for example, has nearly twice the force generating capacity.

Adapted from data contained in: Arnold, E. M., Ward, S. R., Lieber, R. L., & Delp, S. L. (2010). A model of the lower limb for analysis of human movement. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 38(2), 269-279.

What I want to focus on today though is the force generating capacity of the adductors. Summing the peak forces we get 2000N for adductors brevis, longus and magnus working together which is considerably greater the gluteus maximus and up there with the other big muscles. Of course the purpose of muscles is to generate moments and we have to take the moment arm into account as well. The adductors have some of the largest moment arms in the lower limb so their moment generating capacity is even larger than the simple peak force might suggest.

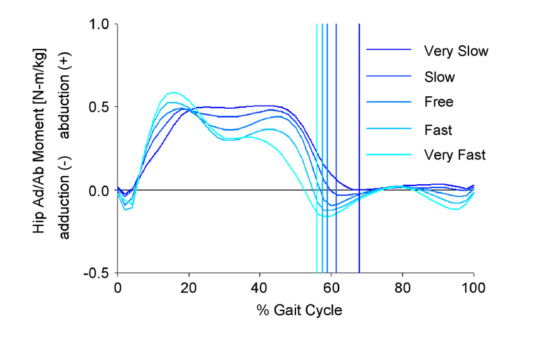

But why do they need to be so large? In both walking (Schwartz, 2008, see figure below) and running (Novacheck 1998) at a range of speeds there is a continuous abductor moment at the hip throughout stance. Indeed because the hip joint is so lateral with respect to the centre of mass of the trunk its very difficult to see how there can be anything other than an internal abductor moment at the hip.

Schwartz, M. H., Rozumalski, A., & Trost, J. P. (2008). The effect of walking speed on the gait of typically developing children. J Biomech, 41(8), 1639-1650.

Anderson and Pandy (2001) in their simulation of human walking found low levels of activation in the adductor magnus. This was confined to a short period around foot contact presumably to supply the small adductor moment immediately after heel contact as seen above. Unsurprisingly in later analysis (2003) of the same data they concluded that the adductors make a negligible contribution to the vertical component of the ground reaction. Liu et al. (2006) who were tracking real data, found that the adductors don’t make any contribution to the vertical or fore-aft component of the ground reaction either at normal walking speed (2006) or a range of walking speeds (2008).

So what’s going on? The adductor magnus is the seventh biggest muscle in the human body and yet it doesn’t seem to do anything during walking or running. There is absolutely no doubt of course that it does come into action during a range of 0ther activities, especially in sport, but how much? Taking the argument above that it is most likely to be needed when the centre of mass of the trunk is lateral to the hip joint then there will be relatively few occasions when this occurs in most sports (and I’d suspect even fewer in non-sporting activities). To get to the size they are the hip adductors must have conferred some evolutionary advantage – but what?

Having written this I’ve been out for a 15km run and guess what – it is my groin (adductors) that is aching. Something really doesn’t add up!

.

Anderson, F. C., & Pandy, M. G. (2001). Dynamic optimization of human walking. J Biomech Eng, 123(5), 381-390.

Anderson, F. C., & Pandy, M. G. (2003). Individual muscle contributions to support in normal walking. Gait Posture, 17(2), 159-169.

Arnold, E. M., Ward, S. R., Lieber, R. L., & Delp, S. L. (2010). A model of the lower limb for analysis of human movement. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 38(2), 269-279.

Liu, M. Q., Anderson, F. C., Pandy, M. G., & Delp, S. L. (2006). Muscles that support the body also modulate forward progression during walking. J Biomech, 39(14), 2623-2630.

Liu, M. Q., Anderson, F. C., Schwartz, M. H., & Delp, S. L. (2008). Muscle contributions to support and progression over a range of walking speeds. J Biomech, 41(15), 3243-3252.

Novacheck, T. F. (1998). The biomechanics of running. Gait Posture, 7(1), 77-95.

Schwartz, M. H., Rozumalski, A., & Trost, J. P. (2008). The effect of walking speed on the gait of typically developing children. J Biomech, 41(8), 1639-1650.